Exploring V8's strings: implementation and optimizations

- 2023-11-14

- en

- CC BY-SA 4.0

- read in russian

JavaScript was always, in one way or another, a text manipulation language - from early web page HTML to modern compilers and tooling. Not a surprise, then, that quite a lot of time was spent tuning and optimizing the string value handling in most modern JS engines.

In this article, I will focus on V8's implementation of strings. I will demonstrate various string optimizations by beating C++ in a totally 100% legit benchmark. Finally, I will demonstrate the ways in which these implementation details might actually perform worse, and how to deal with that.

#Prerequisites

To be able to tell which string implementation V8 is using in any given moment, I will use V8's debug intrinsics. To be able to access those, run Node.js with an --allow-natives-syntax argument.

$ node --allow-natives-syntax

Welcome to Node.js v20.30.

Type ".help" for more information.

> %123

DebugPrint: Smi: 0x7b 123

123

The %DebugPrint() intrinsic writes out quite a lot of info when used on strings. I will only show here the most important bits, using /* ... */ to skip over the others.

#V8's string implementations

Inside V8's source code, there's a handy list of all the string implementations it uses:

StringSeqStringSeqOneByteStringSeqTwoByteString

SlicedStringConsStringThinStringExternalStringExternalOneByteStringExternalTwoByteString

InternalizedStringSeqInternalizedStringSeqOneByteInternalizedStringSeqTwoByteInternalizedString

ConsInternalizedStringExternalInternalizedStringExternalOneByteInternalizedStringExternalTwoByteInternalizedString

Most of those, however, are combinations of several base traits:

#OneByte vs TwoByte

The ECMAScript standard defines a string as a sequence of 16-bit elements. But in a lot of cases, storing 2 bytes per character is a waste of memory. In fact, quite a lot of strings in most code will be limited to ASCII. That is why V8 has both one-byte and two-byte strings.

Here is an example of an ASCII string. Notice its type:

> %"hello"

DebugPrint: 0x209affbb9309: in OldSpace: #hello

0x30f098a80299: in ReadOnlySpace

- type: ONE_BYTE_INTERNALIZED_STRING_TYPE

/* ... */

And here is a non-ASCII one. It has a two-byte representation:

> %"привет"

DebugPrint: 0x1b10a9ba2291: in OldSpace: u#\u043f\u0440\u0438\u0432\u0435\u0442

0x30f098a81e29: in ReadOnlySpace

- type: INTERNALIZED_STRING_TYPE

/* ... */

#Internalized

Some strings - string literals in particular - are internalized by the engine - that is, collected into a single string pool. Whenever you use a particular string literal, the internalized version from this pool is used, instead of allocating a new one every time. Such strings will have an Internalized type:

> %"hello"

DebugPrint: 0x209affbb9309: in OldSpace: #hello

0x30f098a80299: in ReadOnlySpace

- type: ONE_BYTE_INTERNALIZED_STRING_TYPE

/* ... */

If a string value is only known at run time, it (usually) won't be internalized. Notice the absence of INTERNALIZED in its type:

>

> "hello.txt", "hello", "utf8"

>

> %s

DebugPrint: 0x2c6f46782469:: "hello"

0xd2880ec0879: in ReadOnlySpace

- type: ONE_BYTE_STRING_TYPE

/* ... */

It is worth noting that this string can still be internalized. You can force that by turning it into a string literal with eval:

>

undefined

> %ss

DebugPrint: 0x80160fa1809: in OldSpace: #hello

0xd2880ec0299: in ReadOnlySpace

- type: ONE_BYTE_INTERNALIZED_STRING_TYPE

/* ... */

#External

External strings are the ones allocated outside JavaScript's heap. It is usually done for larger strings, to not move them around the memory at garbage collection. To demonstrate such a string, I will artificially limit V8's heap size, and then allocate a large string:

// test.js

// a 16 megabyte string

;

s.length;

# and an 8 megabyte heap

#Sliced

Slicing a string in V8 does not actually copy the data most of the time. Instead, a sliced string is created, storing a reference to a parent string, an offset and a length. Other languages would call that a string view or a string slice.

>

undefined

> %0, 15

DebugPrint: 0x80e9bea9851:: "AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

0xd2880ec1d09: in ReadOnlySpace

- type: SLICED_ONE_BYTE_STRING_TYPE

/* ... */

If, however, the substring is short enough, it's sometimes faster to just copy that tiny bit of data:

> %0, 5

DebugPrint: 0x18a9c2e10169:: "AAAAA"

0xd2880ec0879: in ReadOnlySpace

- type: ONE_BYTE_STRING_TYPE

/* ... */

#Cons

String concatenation is optimized in a similar way. It yields a Cons string, which stores references to its left and right parts:

> %s + s

DebugPrint: 0x2c6f467b3e09:: c"AAAAAAAAAA/* ... */AA"

0xd2880ec1be9: in ReadOnlySpace

- type: CONS_ONE_BYTE_STRING_TYPE

Again, shorter strings are usually just copied outright:

> %0, 2 + 0, 3

DebugPrint: 0xec9b3412501:: "AAAAA"

0xd2880ec0879: in ReadOnlySpace

- type: ONE_BYTE_STRING_TYPE

/* ... */

#Beating C++ with string optimizations

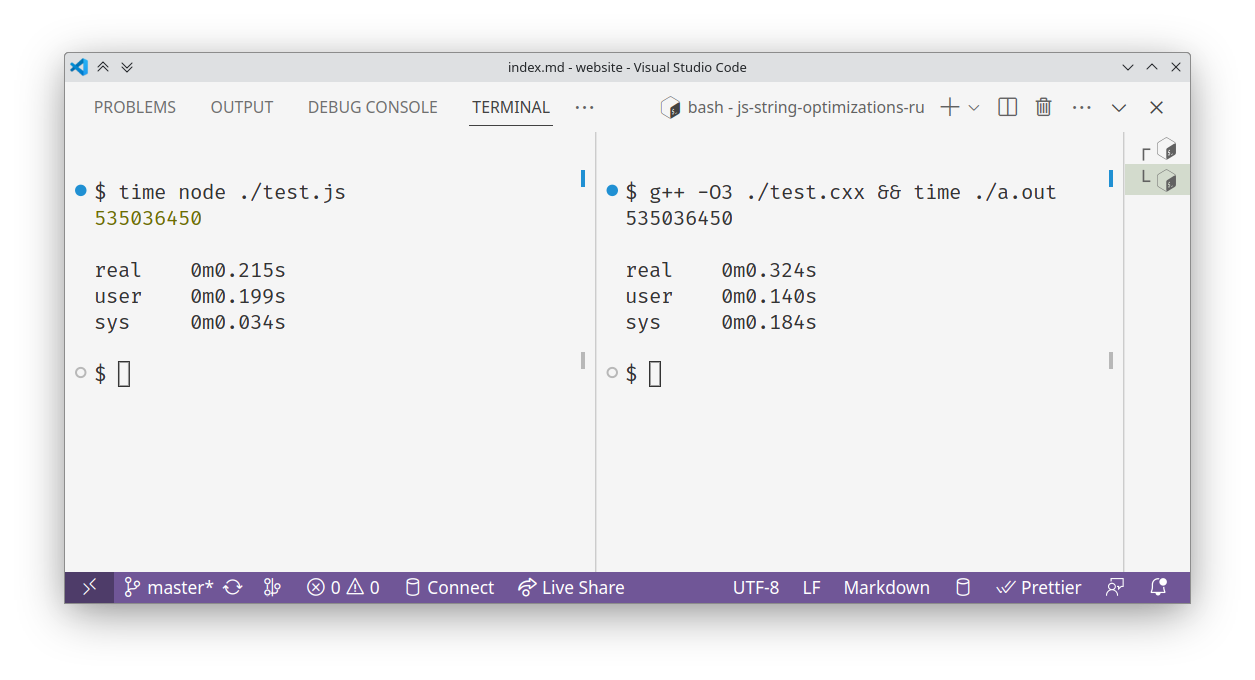

Let's use all that we've learned so far to play a game of Unfair Benchmarks. The rules are simple: we have to think of a specific contrived task where JavaScript, because of its string optimizations, will be faster than the equivalent C++ code.

In our case, we'll exploit the fact that Cons and Sliced string don't copy the data.

// unethical-benchmark.js

// given an ASCII string of length 1500,

// find the total length of those of its substrings

// that are longer than 200 chars

;

;

for ; i < text.length; i++

result.length;

We'll run it on bare V8 using jsvu:

And here is the C++ code, translated line-by-line:

// unethical-benchmark.cxx

// given an ASCII string of length 1500,

// find the total length of those of its substrings

// that are longer than 200 chars

int

&&

This segment is, of course, a joke - both the code and the problem are obviously bad. But it succeeds demonstrating that even the most naive code can be sped up considerably by the V8's string optimizations.

#Unintended side effects, or: how to scrub a string

The downside of such implicit optimizations is, of course, that you can't really control them. In many other languages, a programmer can choose to explicitly use a string view or a string builder where they really need them. But JS has the programmer either hoping the engine is smart enough, or using black magic to force it to do what they want.

To demonstrate one such case, I will first write a simple script that will fetch a couple of web pages, and then extract from them all the linked URLs:

// urls-1.js

;

Let's find out the smallest heap size it will run on:

<-

) ) ) ;

) ) ) ) ()

<-

Looks like 10 megabytes is enough, but 9 isn't.

Let's try to make memory consumption even lower. For example, how about forcing the engine to collect the html data when it's no longer needed?

// urls-2.js

;

<-

) ) ) ;

) ) ) ;

<-

Nothing's changed! And the reason is actually those very string optimizations we discussed earlier. All the urls are actually Sliced strings, and that means they all retain references to the whole of html data!

The solution is to scrub those strings clean!

// urls-3.js

;

Looks like black magic alright. But does it work?

# it works!

<-

) ) ) ;

) ) ) ;

) ) ) ;

<-

As you can see, the code now works fine with a 9 megabyte heap, only OOMing at 7 megabytes. That's two megabytes of RAM reclaimed by forcing the engine to use a specific string implementation.

We can reclaim even more by forcing one-byte representation of all the strings. Even though those string aren't really ASCII, the magic of UTF-8 will ensure our code works like before:

// urls-4.js

;

With that, we have reclaimed another megabyte:

# it works!

<-

) ) ) ;

) ) ) ;

<-

#In conclusion

Most modern JavaScript engines, including V8, have quite a lot of thought put into optimizing various string operations. In my article, I have explored some of those optimizations. While they might be hard to explicitly make use of, it is still quite useful to remember they exist - if only to debug weird and unexpected performance problems.